Israeli Defense

by Yoaz Hendel

Middle East Quarterly

Winter 2012, pp. 31-38 (view PDF)

Editors’ note: Yoaz Hendel now works in the Israeli prime minister’s office. This article was written before his government service; views expressed herein are his alone.

While the Obama administration has not reconciled itself to the futility of curbing Tehran’s nuclear buildup through diplomatic means, most Israelis have given up hope that the international sanctions can dissuade the Islamic Republic from acquiring the means to murder by the millions. Israel’s leadership faces a stark choice—either come to terms with a nuclear Iran or launch a preemptive military strike.

The Begin Doctrine

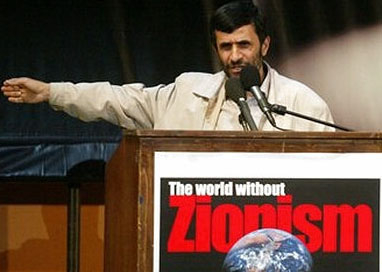

Ahmadinejad delivers his “Wipe Israel from the map” speech at Tehran’s The World without Zionism conference, October 26, 2005. Iran’s genocidal intentions have been repeatedly spelled out by current and former leaders in Tehran, and it is wise for the Israeli leadership to take the rhetoric—combined as it is with the hard facts of Iran’s nuclear subterfuge—seriously. |

When the Israeli Air Force (IAF) decimated Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor thirty years ago, drawing nearly universal condemnation, the government of prime minister Menachem Begin declared Israel’s “determination to prevent confrontation states … from gaining access to nuclear weapons.” Then-defense minister Ariel Sharon explained, “Israel cannot afford the introduction of the nuclear weapon [to the Middle East]. For us, it is not a question of balance of terror but a question of survival. We shall, therefore, have to prevent such a threat at its inception”[1]

This preventive counter-proliferation doctrine is rooted in both geostrategic logic and historical memory. A small country the size of New Jersey, with most of its inhabitants concentrated in one central area, Israel is highly vulnerable to nuclear attack. Furthermore, the depth of hostility to Israel in the Muslim Middle East is such that its enemies have been highly disposed to brinksmanship and risk-taking. Given the Jewish people’s long history of horrific mass victimization, most Israelis find it deeply unsettling to face the threat of annihilation again.

While the alleged 2007 bombing of Syria’s al-Kibar reactor underscored Jerusalem’s willingness to take military action in preventing its enemies from developing nuclear weapons, its counter-proliferation efforts have relied heavily on diplomacy and covert operations. The raid on Osirak came only after the failure of Israeli efforts to dissuade or prevent France from providing the necessary hardware. Likewise, the Israelis have reportedly been responsible for the assassinations of several Iranian nuclear scientists in recent years.[2] They reportedly helped create the Stuxnet computer worm, dubbed by The New York Times “the most sophisticated cyber weapon ever deployed,” which caused major setbacks to Iran’s uranium enrichment program in 2009.[3] However, such methods can only slow Tehran’s progress, not halt or reverse it.

The Iranian Threat

Tehran has already reached what Brig. Gen. (res.) Shlomo Brom has called the “point of irreversibility” at which time the proliferator “stops being dependent on external assistance” to produce the bomb.[4] Most Israeli officials believe that no combination of likely external incentives or disincentives can persuade the Iranians to verifiably abandon the effort. The Iranian regime has every reason to persevere in its pursuit of the ultimate weapon. While the world condemned North Korea’s development of nuclear weapons, it was unwilling to apply sufficient penalties to dissuade Pyongyang from building the bomb.

The regime has an impressive ballistic missile program for delivering weapons of mass destruction. The Iranians began equipping themselves with SCUD missiles during the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war.[5] Afterward, it turned to North Korea for both missiles and the technology to set up its own research and production facilities. Tehran has produced hundreds of Shahab-3 missiles, which have a range of nearly 1,000 miles and can carry a warhead weighing from 500 kilograms to one ton.[6] In 2009, Tehran successfully tested a new two-stage, solid propellant missile, the Sejil-2, which has a range of over 1,200 miles, placing parts of Europe within its reach.

There is some disagreement as to how long it will take Tehran to produce a nuclear weapon. While the government of Israel has claimed that Iran is within a year or two of this goal, in January 2011, outgoing Mossad director Meir Dagan alleged that Iran will be unable to attain it before 2015.[7]

Iranian Intentions

Much of the debate in Israel is focused on the question of Iranian intentions. The fact that Tehran has poured staggering amounts of money, human capital, and industrial might into nuclear development—at the expense of its conventional military strength, which has many gaps, not to mention the wider Iranian economy—is by itself a troubling indicator of its priorities. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and many other leading Israeli political and security figures view the Islamic Republic as so unremittingly hostile that “everything else pales” before the threat posed by its pursuit of nuclear weapons.[8]

Proponents of this view draw upon repeated threats by President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to wipe Israel off the map[9] and Iranian support for radical Palestinian and Lebanese groups seeking its destruction. They also point to Ahmadinejad’s radical millenarian strand of Shiite Islamism.[10] Shiites believe that the twelfth of a succession of imams directly descendant of the Prophet Muhammad went into hiding in the ninth century and will one day return to this world after a period of cataclysmic war to usher in an era of stability and peace.

Ahmadinejad appears to believe that this day will happen in his lifetime. In 2004, as mayor of Tehran, he ordered the construction of a grand avenue in the city center, supposedly to welcome the Mahdi on the day of his reappearance. As president, he allocated $17 million for a mosque closely associated with the Mahdi in the city of Jamkaran.[11] Rather than seeking to reassure the world about Tehran’s peaceful intentions during his 2007 address before the U.N. General Assembly, Ahmadinejad embarked on a wide-eyed discourse about the wonders of the Twelfth Imam: “There will come a time when justice will prevail across the globe … under the rule of the perfect man, the last divine source on earth, the Mahdi.”[12]

The fear in Israel is that someone who firmly believes an apocalyptic showdown between good and evil is inevitable and divinely ordained will not be easily deterred by the threat of a nuclear war. “There are new calls for the extermination of the Jewish State,” Netanyahu warned during a January 2010 visit to Israel’s Holocaust museum, Yad Vashem. “This is certainly our concern, but it is not only our concern.”[13] For Netanyahu, a nuclear Iran is a clear and present existential threat.

Those who dissent from this view point out that the Iranian people are not particularly hostile to Israelis; indeed, the two countries enjoyed close relations before the 1979 Iranian revolution. They argue that the Iranian regime’s militant anti-Zionism is a vehicle for gaining influence in the predominantly Sunni Arab Middle East but not something that would drive its leaders to commit suicide. “I am not underestimating the significance of a nuclear Iran, but we should not give it Holocaust subtext like politicians try to do,” said former Israel Defense Forces (IDF) chief of staff Dan Halutz, who commanded the Israeli military during the war in Lebanon in 2006.[14] Defense Minister Ehud Barak said in a widely circulated September 2009 interview that Iran was not an “existential” threat to Israel.[15]

The question of whether Iran is an existential danger is more rhetorical than substantive. Even if Iranian nuclear weapons are never fired, their mere existence would be a profound blow to most Israelis’ sense of security. In one poll, 27 percent of Israelis said they would consider leaving the country if Tehran developed nuclear capabilities. Loss of investor confidence would damage the economy. This could spell the failure of Zionism’s mission of providing a Jewish refuge as Jews will look to the Diaspora for safety.[16] This is precisely why Israel’s enemies salivate over the possibility of an Iranian bomb.

Even if the prospect of mutually assured destruction effectively rules out an Iranian first strike, Tehran’s acquisition of nuclear weapons would still shift the balance of power greatly. Iran projects its power throughout the Middle East mainly by way of allies and proxies, such as Muqtada al-Sadr’s Mahdi army in Iraq, Hamas in Gaza, the Assad regime in Syria, and Hezbollah in Lebanon. The Iranian nuclear umbrella will embolden them. The next time an Israeli soldier is abducted in a cross-border attack by Hezbollah or Hamas, Jerusalem will have to weigh the risks of a nuclear escalation before responding. There is also the possibility that Tehran could provide a nuclear device to one of its terrorist proxies.[17]

A successful Iranian bid to acquire the bomb will set off an unprecedented nuclear arms race throughout the region. Arab countries such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and the United Arab Emirates will want to create their own nuclear insurance policies in the face of Tehran’s belligerence and regional ambitions. Turkey has passed a bill in its parliament paving the way for the construction of three nuclear reactors by 2020.[18]

Most of Israel’s decision-makers believe that Israel cannot afford the risks of living with a nuclear Iran. Those who publicly differ with Netanyahu on this score seem mainly concerned that he is exploiting popular fears for political gain, but they are likely to fall in line with public opinion at the end of the day. The large majority of Israelis support a military strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities as a last resort, and a small majority (51 percent according to a 2009 poll) favor an immediate strike on Iran as a first resort.[19]

The Military Option

The general assessment is that the IDF has the ability to knock out some of Tehran’s key nuclear facilities and set back its nuclear program by a couple of years but not completely destroy it—at least not in one strike.[20] Several factors make Iran’s nuclear program much more difficult to incapacitate than that of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

Whereas most of Iraq’s vital nuclear assets were concentrated at Osirak, “Iran’s nuclear facilities are spread out,” notes former IDF chief of staff Ya’alon,[21] some of them in close proximity to population centers. The distance to targets in Iran would be considerably greater than to Osirak, and its facilities are better defended. Iran has mastered nuclear technology much more thoroughly than Iraq and can, therefore, repair much of the damage without external help.

Of the known Iranian nuclear sites, five main facilities are almost certain to be targeted in any preemptive strike. The first is the Bushehr light-water reactor, along the gulf coast of southwestern Iran. The second is the heavy-water plant under construction near the town of Arak, which would be instrumental to production of plutonium. Next is the uranium conversion facility at Isfahan. Based on satellite imagery, the facility is above ground although some reports have suggested tunneling near the complex.[22]

Fourth is the uranium enrichment facility at Qom, which the Iranians concealed from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) prior to September 2009 and well after major Western intelligence agencies knew about it. The facility, which can hold about 3,000 centrifuges, was built into a mountain, making it difficult to penetrate. Israeli defense minister Barak called it “immune to standard bombs.”[23]

The fifth and most heavily fortified primary target is the main Iranian uranium enrichment facility in Natanz. The complex consists of two large halls, roughly 300,000 square feet each, dug somewhere between eight and twenty-three feet below ground and covered by several layers of concrete and metal. The walls of each hall are estimated to be approximately two feet thick. The facility is also surrounded by short-range, Russian-made TOR-M surface-to-air missiles.

Military planners may also feel compelled to attack Tehran’s centrifuge fabrication sites since their destruction would hamper the efforts to reestablish its nuclear program. However, it is believed that the Iranians have dispersed some centrifuges to underground sites not declared to the IAEA. It is by no means clear that Israeli intelligence has a full accounting of where they are.

The Israelis may also choose to bomb Iranian radar stations and air bases in order to knock out Tehran’s ability to defend its skies, particularly if multiple waves are required. Ya’alon estimates that Israel would need to attack a few dozen sites.[24]

The Operation

The Israeli Air Force is capable of striking the necessary targets with two to three full squadrons of fighter-bombers with escorts to shoot down enemy aircraft; however, most of the escorts will require refueling to strike the necessary targets in Iran.[25] In addition, the Israelis can make use of ballistic missiles and cruise missiles from their Dolphin-class submarines.

The IAF has carried out long-range missions in the past. In 1981, Israeli F-16s struck the Osirak reactor without midair refueling. Refueling tankers were activated for Israel’s longest-range air strike to date, the 1985 bombing of the Palestine Liberation Organization’s (PLO) headquarters in Tunis, 1,500 miles away. The IAF’s highly publicized 2009 flyover over Gibraltar was widely perceived as a dress rehearsal for a strike against Iran.[26] In 2009, the IAF instituted a new training regimen that included refueling planes as their engines were on and sitting on the runway with fuel nozzles disconnected seconds before takeoff.

The IAF has specialized munitions designed to penetrate fortified targets, including GBU-27 and GBU-28 laser-guided bunker buster bombs and various domestically produced ordnance. Israeli pilots are skilled at using successive missile strikes to penetrate fortifications. “Even if one bomb would not suffice to penetrate, we could guide other bombs directly to the hole created by the previous ones and eventually destroy any target,” explains former IAF commander Maj. Gen. Eitan Ben-Eliyahu, who participated in the strike on Osirak.[27]

Israel’s advanced electronic-warfare systems are likely to be successful in suppressing Iran’s air defenses although these were significantly upgraded by Moscow during the 2000s.[28] Moreover, whereas thirty years ago, Israeli pilots needed to fly directly over Osirak to drop their bombs, today they can fly at higher altitudes and launch satellite or laser-guided missiles from a safer distance. Nor are Tehran’s roughly 160 operational combat aircraft, mostly antiquated U.S. and French planes, likely to pose a serious threat to Israeli pilots.

Possible Attack Routes

The main problem Jerusalem will encounter in attacking Iran’s nuclear facilities results from the long distance to the main targets. Since greater distance always means that more things can go wrong, Israeli losses and efficacy will likely depend on which of three possible routes they take to Iran.

The northern route runs along the Turkish-Syrian border into Iran and is estimated to be about 1,300 miles. This route entails several risks and would need to take into account Syrian air defenses and Turkish opposition to violating its airspace. Israeli planes flew over Turkey when the IAF bombed al-Kibar in 2007 and even dropped fuel tanks in Turkish territory. However, the recent deterioration in relations between Ankara and Jerusalem makes it extremely unlikely that the Turkish government will allow such an intrusion.

The central route over Jordan and Iraq is the most direct, bringing the distance to Natanz from the IAF’s Hatzerim air base down to about 1,000 miles, yet it entails serious diplomatic obstacles. Jerusalem would have to coordinate either with the Jordanians and the Americans or fly without forewarning. While Israel has a peace treaty with Jordan, Amman will not want to be perceived as cooperating with Israeli military action against Tehran and thus possibly face the brunt of an Iranian reprisal. Washington may not want to be involved either, as it needs Tehran’s acquiescence to withdraw its forces from Iraq successfully. While Jerusalem could limit the risk of hostile fire by notifying its two allies of the impending attack, there would be considerable diplomatic costs.

The southern route would take Israeli planes over Saudi Arabia and then into Iran. While this is longer than the central route, there have been reports that the Saudis have given Jerusalem permission to use their airspace for such an operation.[29]

The difficulties also depend on the precise goal of the air strike. A short-term, financially costly degradation of Iran’s nuclear program can be achieved in one wave of attacks, but Israeli defense analysts have estimated that a decisive blow could require hitting as many as sixty different targets with return sorties lasting up to two days.

Estimates in Israel vary regarding the losses the IAF might suffer in such an operation.[30] Some estimates claim that with their advanced, Russian-supplied air defense systems, the Iranians might be able to shoot down a small number of aircraft. But even just a few pilots shot down and captured by Iran would be a heart-wrenching tragedy for Israelis. To prepare for this, in 2009 the IAF began increasing mental training for its airmen with an emphasis on survival skills.

Many former, high-ranking generals and intelligence chiefs have cast doubt on whether Jerusalem can succeed in decisively setting back Tehran’s nuclear program. Addressing an audience at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in May 2011, Meir Dagan said that the idea of attacking Iranian nuclear sites was “the stupidest thing” he had ever heard and that such an attempt would have a near-zero chance of success.[31]

The Fallout

The strategic fallout from an Israeli attack will likely be significant. Hezbollah will probably initiate hostilities across the Lebanese-Israeli border. During the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war, the Shiite Islamist group fired more than 4,000 rockets into Israel, causing extensive damage and killing forty-four civilians.[32] Today, its arsenal is considerably larger and includes many more rockets capable of reaching Tel Aviv. Dagan estimates that the Iranians can fire missiles at Israel for a period of months, and that Hezbollah can fire tens of thousands of rockets.[33] Hamas may also attack Israel with rockets from Gaza. It is not inconceivable that Syrian president Bashar Assad would join the fight, if still in power, in hope of diverting public anger away from his regime.

Iran has also developed an extensive overseas terrorist network, cultivated in conjunction with Hezbollah. This network was responsible for two car bombings against the Jewish community in Argentina that left 114 people dead in the early 1990s.[34]

Last year, Israel distributed gas masks to prepare for the possibility that Iran or Syria would deploy chemical or biological weapons[35] while the IDF’s Home Front Command received an increased budget to prepare bomb shelters and teach the public what to do in case of emergency.[36] C4I systems were improved between early-warning missile detection systems and air sirens, including specially designed radars that can accurately predict the exact landing site of incoming missiles. Since no one is certain how accurate Iran’s Shahab and Sajil missiles are, Jerusalem began strengthening defenses at its Dimona nuclear reactor in 2008.[37]

Jerusalem will not sit back and allow its citizens to be bombed mercilessly. Since Lebanon will probably be the main platform of any major Iranian attack, Israeli retaliation there is sure to be swift and expansive. Should Syria offer up any form of direct participation in the war, it too may come under Israeli attack. The Israelis may go so far as to bomb Iran’s oil fields and energy infrastructure. Since oil receipts provide at least 75 percent of the Iranian regime’s income and at least 80 percent of export revenues, the political shock of losing this income could lead the regime to rethink its nuclear stance, as well as erode its public support, and make it more difficult to finance the repair of damaged nuclear facilities.[38]

On the other hand, Tehran may double down by sending its own ground troops to Lebanon or Syria to join the fight against Israel. This could draw in the Persian Gulf Arab monarchies, particularly if the Alawite-led Assad regime is still facing active opposition from its majority Sunni population.

How long such a war will last is impossible to predict. Israel’s defense doctrine calls for short wars, so it will likely launch a diplomatic campaign with Western backing to end the war as soon as possible. However, the Iranians may hunker down for the long haul, much as they did during the 8-year Iran-Iraq war.[39]

If a military solution cannot guarantee success at an acceptable price, some in Israel argue that the best hope for countering the threat posed by Iranian nuclear weapons is regime change. “The nuclear matter will resolve itself once there is a regime change,” says Uri Lubrani, Israel’s former ambassador to Iran and a senior advisor to the Israeli defense minister until last year. According to Lubrani, the highest priority for Israel and the West should be to strengthen the Iranian masses that rose up in protest following the fraudulent June 2009 elections.[40]

“A military strike will at best delay Iran’s nuclear program, but what’s worse, it will rally the Iranian people to the defense of the regime,” says Lubrani. He argues that it is better to let sanctions eat away at the regime’s legitimacy even if they do not lead to a stand down on its nuclear program.[41]

However, it is not clear whether Lubrani is correct in his assessment that war will benefit the regime. While most Iranians are generally supportive of their country’s nuclear ambitions, devastating Israeli air strikes may drive home the folly of their government’s reckless provocations just as they did during the later stages of the Iran-Iraq war. It is unlikely that many are willing to sacrifice their country’s well-being in pursuit of the bomb.

Whether an Israeli attack will unite the public for or against President Ahmadinejad and Supreme Leader Ali Khamene’i is anyone’s guess. Much will depend on whether the air strikes produce significant collateral damage. The Bushehr, Isfahan, and Natanz facilities contain uranium hexafluoride (UF6) and even some low-enriched uranium, the release of which into the environment would almost certainly raise public health concerns.

Conclusion

The Israelis will ultimately have to choose between launching an attack likely to spark a large-scale regional conflict and allowing Iran to go nuclear with dire long-term implications. Notwithstanding some disagreement about the immediacy of the threat and possible repercussions, the large majority of Israelis favor military action over living with the ubiquitous threat of nuclear annihilation.

With a U.N. vote on Palestinian statehood threatening to erode Israel’s international standing still further, attacking Iran could prove dangerously isolating for Israel even with Washington’s blessing—to proceed without it would be a step into the unknown. Much, therefore, depends on whether policymakers in Washington will stand by Jerusalem when push eventually comes to shove.

The American people have increasingly come to recognize the threat to world peace posed by Iran. Whereas 6 percent of Americans named Iran as the country that poses the greatest threat to the United States in 1990, in 2006, Iran led the field with 27 percent.[42] However, though Washington’s official stance is that all options remain on the table, Obama is unlikely to undertake direct military action to stop Tehran from building the bomb and may prove reluctant to tacitly support Israeli action.

That is why the decision will ultimately be left to Israel, or rather to its prime minister, who will be faced with a Churchillian dilemma, unprecedented in the Jewish state’s history.

Yoaz Hendel, a military historian who has lectured at Bar Ilan University and written on strategic affairs for the newspaper Yediot Aharonot, now works in the Israeli prime minister’s office. This article was written before his government service; views expressed herein are his alone.

[1] Ariel Sharon, address, Government Press Office, Jerusalem, Dec. 15, 1981.

[2] The Sunday Times (London), Feb. 4, 2007; The Washington Post, Nov. 29, 2010; The Observer (London), Dec. 5, 2010.

[3] The New York Times, Jan. 16, 2011.

[4] Shlomo Brom, “Is the Begin Doctrine Still a Viable Option for Israel?” in Henry Sokolski and Patrick Clawson, eds., Getting Ready for a Nuclear-Ready Iran (Carlisle, Pa.: U.S. Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute, 2005), p. 139.

[5] Yiftah S. Shapir, “Iran”s Ballistic Missiles,” Strategic Assessment INSS, Aug. 2009.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ha’aretz (Tel Aviv), Jan. 7, 2011.

[8] Ibid., Nov. 14, 2006.

[9] Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (Tehran), Oct. 27, 2005.

[10] See Mohebat Ahdiyyih, “Ahmadinejad and the Mahdi,” Middle East Quarterly, Fall 2008, pp. 27-36.

[11] Charles Krauthammer, “In Iran, Arming for Armageddon,” The Washington Post, Dec. 16, 2005.

[12] Islamic Republic News Agency, Sept. 26, 2007.

[13] Benjamin Netanyahu, speech, Jerusalem, Jan. 25, 2010.

[14] The Jerusalem Post, Oct. 15, 2010.

[15] Reuters, Sept. 17, 2009.

[16] Yossi Klein Halevi and Michael B. Oren, “Israel Cannot Live with a Nuclear Iran,” The New Republic, Jan. 26, 2010.

[17] Chuck Freilich “The Armageddon Scenario: Israel and the Threat of Nuclear Terrorism,” BESA Center Perspectives Papers (Ramat Gan), Apr. 8, 2010.

[18] See Yoel Guzansky, “The Saudi Nuclear Option,” INSS Insight, Institute for National Security Studies, National Defense University, Washington, D.C., Apr. 2010; John Bolton, “Get Ready for a Nuclear Iran,” The Wall Street Journal, May 2, 2010.

[19] YNet News (Tel Aviv), May 24, 2009.

[20] Whitney Raas and Austin Long, “Osirak Redux? Assessing Israeli Capabilities to Destroy Iranian Nuclear Facilities,” International Security, Spring 2007, pp. 7-33.

[21] Jane’s Defence Weekly (London), Mar. 10, 2006.

[22] The New York Times, Jan. 5, 2010.

[23] The Jerusalem Post, Dec. 28, 2009.

[24] Jane’s Defence Weekly, Mar. 10, 2006.

[25] Raas and Long, “Osirak Redux?” pp. 7-34.

[26] Ynet News, Mar. 5, 2009.

[27] Jane’s Defense Weekly, Mar. 4, 2005.

[28] Anthony H. Cordesman, “The Iran Attack Plan,” The Wall Street Journal, Sept. 25, 2009.

[29] The Sunday Times, June 12, 2010.

[30] Brom, “Is the Begin Doctrine Still a Viable Option for Israel?” pp. 148-9.

[31] Ha’aretz, May 7, 2011; The Jewish Daily Forward (New York), May 20, 2011.

[32] Fox News, Mar. 27, 2008; The Guardian (London), Apr. 11, 2011.

[33] Ha’aretz, May 7, 2011.

[34] BBC News, Mar. 27, 2011.

[35] Ha’aretz, May 1, 2010.

[36] Ha’aretz, June 17, 2009; “Israeli Civilians Prepare for Life-Threatening Scenarios,” Israel Defense Forces Spokesperson’s Unit, June 22, 2011.

[37] Pakistan Daily (Lahore), Oct. 3, 2008.

[38] Patrick Clawson and Michael Eisenstadt, “The Last Resort,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Washington, D.C., June 2008.

[39] Moshe Vered, “Ending an Iranian-Israeli War,” Mideast Security and Policy Studies, Sept. 2009.

[40] David Horovitz, “Editor’s Notes: Playing Chess against Tehran,” interview with Uri Lubrani, Mar. 11, 2011; The Wall Street Journal, Mar. 13, 2010.

[41] The Wall Street Journal, Mar. 13, 2010.

[42] Associated Press, July 2, 2006.